Development and Morphogensis

About

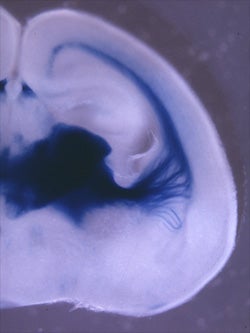

A slice of the brain of a newborn mouse carrying

the reporter, TCA-TLZ, shows the thalamic axons projecting to the cerebral cortex.

Courtesy of Dwyer lab.

How a fertilized egg produces the myriad cell types that make up a complex organism remains one of the fundamental questions of biology. This process requires that cells divide, differentiate, and organize themselves into structures of the appropriate size and shape. For development to proceed normally, information must be integrated at many different biological levels: gene activity, cellular signaling and function, tissue organization, systemic endocrine signals, and environmental inputs. The coordination of information at each of these levels is essential for biological function. For instance, the polarized orientation of sensory epithelial cells in the cochlea requires that these cells synchronize their direction with neighboring sensory cells to produce an ordered array of sensory stereocilia. The precise polarity of this structure is essential for hearing function.

The last half-century of research in the biological sciences has sparked remarkable advances in our understanding of how the cells and tissues of living organisms arise and cooperate to perform a staggering array of specialized functions. The availability of approaches used to elucidate the functions of single genes and gene products, together with technologies that make possible analyses of entire genomes has ushered in an exciting new era of discovery. Thus, many of the most complex secrets of living systems are becoming tractable. One of the most enduring of these problems concerns how “communities” of increasingly specialized cells assemble over time into the recognizable structures we typically associate with biological “form”. This process is termed morphogenesis, and encompasses multiple scales of biological organization from single cells to tissues, organs, organ systems and whole organisms. For example, how do cells self assemble to form tubular structures like the gut or blood vessels of the body? What controls the shapes and sizes of organs such as kidneys, lungs and skeletal structures? Why are some animals able to generate whole limbs and other body parts even as adults, while mammals have only a limited capacity to do so?

Researchers in the Department of Cell Biology are tackling similar questions using a variety of organisms and experimental systems, and by applying broad expertise in manipulating gene expression and in high-resolution imaging in order to better understand the development and morphogenesis of living cells and tissues. These capabilities reflect our established strengths in the fields of developmental biology, cell adhesion and migration, mechanobiology, and cell and tissue polarity. We are confident that knowledge gained from studies in these areas will help prevent birth defects, control cancerous tissue growth, slow the deterioration and aging of tissues, facilitate the repair, regeneration and replacement of injured tissues, and in the long run even allow us to produce replacement tissues and organs outside of the body.

Faculty

Deppmann, Christopher

Elucidating and Understanding the Mechanisms Underlying Nervous System Development

DeSimone, Douglas W.

Cell Adhesion and Adhesion-Dependent Cell Signaling in Vertebrate Morphogenesis

Kucenas, Sarah C

The role of glia in the development, maintenance and regeneration of the nervous system

Lu, Xiaowei

Wnt/PCP signaling in inner ear development Mouse models for human deafness Wnt/PCP signaling in neural tube closure

Winckler, Bettina

Endosomal function and dysfunction in neurons. Development of the nervous system: cytoskeleton and membrane traffic in axon and dendrite growth.

Wotton, David

Regulation of Gene Expression, Development and Tumor Progression by TGF beta Signaling