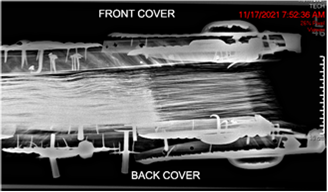

Left: the front cover of the medieval choir book (Medieval choir books, ca. 1450-ca. 1525, Accession #229, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va). Right: an image from a CT scan of the medieval psalter, revealing hidden details.

UVA diagnostic technologist Gordon Songer and CT technologist Brandie Powell are experts at positioning and imaging patients, creating high-quality medical images that radiologists and other physicians can then interpret to help diagnose and treat disease.

One morning in late November 2021, Songer and Powell found themselves imaging a very different kind of patient. Or rather, not a patient at all, but a large and heavily decorated medieval book, dating from 15th-century Italy. Clearly, it was not a typical day in the radiology department.

Gifts from a University Benefactor

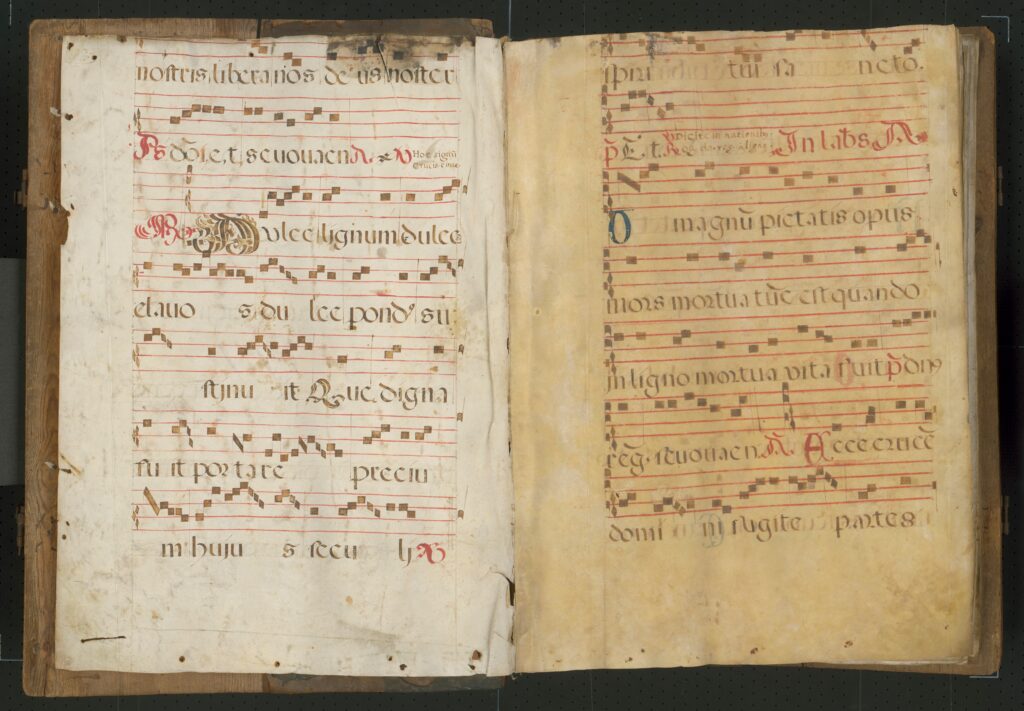

An interior page of the medieval choir book (Medieval choir books, ca. 1450-ca. 1525, Accession #229, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va)

The story of how this five-hundred-year-old medieval manuscript made its way to central Virginia and the University of Virginia is an incomplete one. The paper trail begins and ends with Paul Goodloe McIntire, a Charlottesville native (and, for one session in 1878-79, a UVA student), stockbroker and philanthropist. Among many major gifts he made to the university were a founding gift for the McIntire School of Commerce, a gift for the McIntire Amphitheatre, and the endowment of a fine arts chair, which led to both the music and arts departments at UVA being named after him.

In 1938, McIntire donated two medieval volumes to the UVA Library. David Whitesell, Curator in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at UVA, explains that how McIntire came to acquire the volumes is a bit of a mystery.

“He was not a collector of rare books and manuscripts, as far as we know,” Whitesell explains. “But he likely understood that UVA would benefit by having these two manuscripts on hand for research and instruction—as has been the case.”

The front cover of the psalter (Medieval choir books, ca. 1450-ca. 1525, Accession #229, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va)

Prior to 1938, the manuscripts’ movements and origins are murkier. They are Italian, and based on the handwriting and style of illumination (which refers to elaborate decoration added in painted colors and gold leaf), Whitesell thinks it’s likely they date from the late 15th century. They would have been commissioned for a Roman Catholic church or religious community. The books were hand-made by a team of scribes, who wrote the text, and illuminators, who added the decoration, in a workshop specializing in manuscript production.

The first volume, which is the one Gordon Songer and Brandie Powell imaged, is a choir book. It contains notated music that would have been used for group singing by a choir in a church. The second volume is a psalter, a book containing The Book of Psalms set to music. In both volumes, the musical notation and words are very large so that they could be read at a distance. And the books themselves are substantial objects: the choir book measures two feet long by one-and-a-half feet wide, and is over five inches thick.

But the books’ movements between their creation in Italy and 1938, when McIntire donated them, are unknown. “Illuminated manuscripts have always been prized by collectors,” says Whitesell. “It is a bit sad, but typical for old books and manuscripts, that we cannot tell precisely where these manuscripts have been, and who owned them, during the four centuries before they came to UVA.”

Revealing Secret Histories

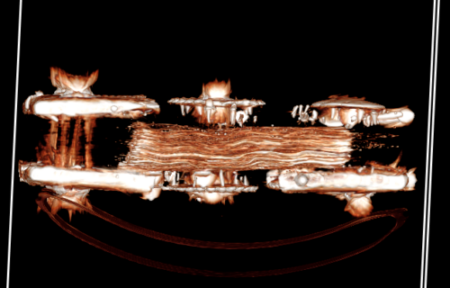

An image from a CT scan of the choir book, showing the metal embellishments, nails, and even the faint lines of ink inside the book’s pages.

Of course, books and other historical objects cannot literally tell us where they have been or what may have been done to them. But as physical objects, clues and signs of their histories are left behind in their materials and the ways they have been manipulated over time.

Sue Donovan is the Conservator for Special Collections at UVA. It was her idea to use x-ray imaging to help assess the condition of the illuminated choir book.

For book and paper conservators like Donovan, x-rays are not commonly used. “We’re usually working with materials that are not very dense,” she says, “and we can usually look inside of them ourselves.”

But these books are not typical books. They are highly decorated and covered in many different and dense materials. “They are very sturdily bound in thick wooden boards covered in calfskin,” Whitesell explains, “with iron spikes and brass bosses (protective metal plates).” They also feature iron clasps to hold the volumes closed when not in use.

These materials made x-ray an intriguing possibility. Donovan thought back to an item made of cloth nailed into wood that Special Collections had UVA technologists x-ray some three years earlier. She wondered if x-rays could again prove useful. So she contacted Anthony Calise, an Imaging Supervisor for Diagnostic Radiology in the UVA Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, who was involved with imaging the item.

In late November, the choir book was brought to the Emergency Department at UVA Health. Technologist Gordon Songer carefully positioned the book under an x-ray scanner and imaged it. Calise suggested using a CT scanner to image the volume as well, which would create a 3-dimensional representation of the book that conservators could move around and view from any angle.

“It was really exciting to do something with this historical aspect,” says Calise. “It broke up some of the monotony of COVID-19, and allowed us to do something more relaxed and fun.”

For Donovan, getting the images from radiology was both affirming and exhilarating.

“It did exactly what I wanted it to do, but even more than that,” she says. “I could see how the metalwork is attached, how deep the nails go. I could see if there were nails I couldn’t see by eye. It gives me a lot of information, moving forward, about how I can actually apply new materials in order to make the book more stable. And it allowed me to tell my colleagues exactly what I wanted to do and how I wanted to do it.”

Even things that Donovan already knew about the book took on a different dimension when she saw them depicted on the x-rays.

“I saw the presence of some kind of metal inside the book itself,” she says. “Not the coverings on the outside, but something within the pages. It took me a while to realize that it was the ink that they used to write the book itself, which has metal in it. I knew it was there, but it was really beautiful to see it on the x-ray.”

Conserving These Books for the Next Generation

The interior of the psalter (Medieval choir books, ca. 1450-ca. 1525, Accession #229, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va)

Because of their relative completeness and aesthetic beauty, the two books that McIntire donated are unique among the medieval books in Special Collections. And they are frequently used in a diverse range of UVA classes.

“They’re often shown to undergraduate and graduate classes in music, medieval studies, history, religious studies and classics,” says Whitesell, ”as well as summer Rare Book School courses on the history of books and manuscripts, and outside groups desiring to use our collections or learn more about them.”

“Because they are so visually interesting, intriguing and appealing, they are always a highlight of a class or tour,” Whitesell continues. “We do have to restrict their handling and use them carefully—the bindings are more fragile than they look—but there is no better way to understand how they were made and used than to examine them up close.”

With this in mind, Donovan is not trying to change much in her treatment of the choir book. “It’s a hybrid approach,” she says. “I’m not taking it apart and putting it back together again. I am working with what I have, specifically because it is such an important volume for material culture.”

She plans to lift pieces of leather off the spine that are already detaching and haven’t been functional for many years. When those are lifted up, she can access the sewing underneath and add in stronger materials to solidify and stabilize the volume. Then she will put the original leather material back on top so that the book appears unchanged.

Being able to see on the x-ray where exactly the nails are, or the spine lining is, for example, tells her precisely where she should avoid using a water-based adhesive in her treatment, because it could activate the iron in the nails and cause rusting.

“For me, as a conservator, I’m trying to get the most information possible before starting a treatment,” Donovan says. “Especially when it’s a book like this one, which gets used so much in instruction.”

“This book, with its beautiful metal embellishments, huge wooden boards, and leather bindings, is essential to show to the current generation who may have never seen books like this before,” she says. “They’ve grown up reading on Kindles and the internet. This book shows them the long trajectory of books as we know them today. And when the treatments are complete, it will be ready for new generations to see for themselves.”

Comments