Causes of Chronic Constipation

Why do children become constipated?

Many parents have been told their child became constipated because of drinking too much milk or eating too much cheese. What we eat affects our bowel habits, but diet alone is usually not the cause of chronic constipation. As a group, children who develop chronic constipation tend to drink less fluid than children who do not become constipated, but in most cases it is not until the child begins to associate pain with passing bowel movements that constipation develops.

There are other reasons that children may become constipated but they are very uncommon:

- Hirschsprung’s disease

- Neurological abnormalities

- Hypothyroidism

Most of the time, pain with bowel movements starts when a child passes a very big or hard bowel movement. There are lots of reasons this might happen:

Most of the time, pain with bowel movements starts when a child passes a very big or hard bowel movement. There are lots of reasons this might happen:

In young infants, a severe case of diaper rash may cause some small tears or rips (anal fissures) to develop at the anus. These rips can be extremely painful – like “paper cuts” on your fingers. Older children may develop anal fissures following a bout of diarrhea or when they pass a very large bowel movement that forces the anal sphincter to open too wide.

When a young infant’s diet changes from breast milk to formula, or from formula to cow’s milk, bowel movements often become much harder. This also happens in older children when when they begin eating solid foods.

As toddlers go through toilet training, they may hold back too long causing their bowel movements to become large and/or hard. This may also happen when children enter pre-school or kindergarten because many children will not go to the bathroom at school (lots of adults won’t go to the bathroom at work or in a public place).

Following a bout of diarrhea, some children get a little dehydrated and as the diarrhea goes away, the intestine does what it is supposed to do and absorbs salt and water. This causes the bowel movement to become harder. This can also happen after surgery or some other traumatic event.

It really doesn’t matter why the pain starts. . . what is important is that the child passes a big and/or hard bowel movement and it hurts! Children are smart people, and if something hurts, they at least wonder whether they should do it again.

How does the cycle of chronic constipation occur?

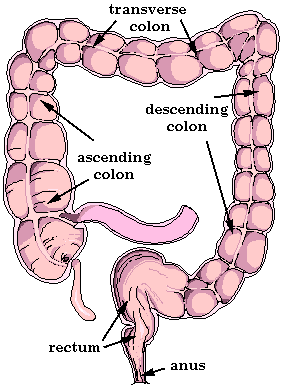

This drawing shows the large intestine, also called the “colon”. We refer to parts of the colon in the discussion below.

Once children begin to fear passing a bowel movement, the cycle of chronic constipation has begun. The child may continue to pass bowel movements fairly regularly, but if it hurts, they often hold back and don’t completely empty themselves when they go to the bathroom (withholding). The large intestine slowly fills with stool and stretches out of shape. If you stretch your intestine suddenly, it hurts and gives you “cramps”. However, if you stretch your intestine slowly, it doesn’t hurt or give you cramps.

Once children begin to fear passing a bowel movement, the cycle of chronic constipation has begun. The child may continue to pass bowel movements fairly regularly, but if it hurts, they often hold back and don’t completely empty themselves when they go to the bathroom (withholding). The large intestine slowly fills with stool and stretches out of shape. If you stretch your intestine suddenly, it hurts and gives you “cramps”. However, if you stretch your intestine slowly, it doesn’t hurt or give you cramps.

This slow stretching of the large intestine causes its walls to relax by “accommodating”, and the intestine becomes bigger and bigger (called megacolon). This explains why children with chronic constipation can pass bowel movements that are extremely large, often larger than those of adults.

Normally, when we pass a bowel movement, we completely empty the bottom of our large intestine (rectum). Most of the time the rectum remains empty. Once a day, twice a day, or every other day, some stool moves into the empty rectum and stretches it, causing the “feeling” or “urge” to go to the bathroom (drawing at right). When things work correctly, the “urge” to go to the bathroom comes on slowly and it doesn’t hurt. You respond to the “urge” by going to the bathroom and passing a bowel movement which empties your rectum.

Children with chronic constipation almost always have stool in the rectum. The nerves that send the signal to the brain are constantly being stimulated so they are constantly getting the signal to go to the bathroom. Over time, the child “learns” to ignore this signal. This is not a conscious decision, but something that just happens. It is like sitting in a room with a buzzing light. For the first few days, you hear the buzzing, but after a while, you tune it out. After a while, children tune out the signal to pass a bowel movement. Once this happens, the urge to go to the bathroom comes in a very different way: when the large intestine gets critically stretched — so much that it basically says “I can’t take it any more!” — this feeling hurts, it is cramps.

In most children, this type of urge comes on suddenly and is very uncomfortable. When young children get this feeling, they may become very unhappy, begin sweating or become pale, disappear into a quiet room or closet, or grab hold of the back of a chair or another piece of the furniture and stand on their tip toes. These are all responses to the pain they are experiencing.

In most children, this type of urge comes on suddenly and is very uncomfortable. When young children get this feeling, they may become very unhappy, begin sweating or become pale, disappear into a quiet room or closet, or grab hold of the back of a chair or another piece of the furniture and stand on their tip toes. These are all responses to the pain they are experiencing.

They are having cramps and a tremendous urge to pass a bowel movement, but because of the pain associated with passing bowel movements, they are holding back. They are holding back not out of spite, but out of fear!

Eventually, the child will pass a bowel movement, but it is often very large and very hard, so there will be lots of pain. This reinforces the child’s fear, so the problem will go on and on and on . . . as the cycle of pain and fear continues, passing bowel movements becomes more and more abnormal.

People who don’t have trouble passing bowel movements don’t think about it much, but it is a complicated process. Basically, three things must happen:

- We must get the urge to pass a bowel movement.

- Once we feel the urge and decide to go, we increase the pressure in the large intestine to push the bowel movement out. To increase the pressure we must use many different muscles working together. We take in a breath and push down with our diaphragms. We tighten all the muscles of the abdominal wall and push downward. At the same time, we are lifting and relaxing a number of muscles in the pelvis.

- At the same time we are pushing or straining, we must relax the external anal sphincter. This is the muscle at the very bottom of the rectum that keeps stool inside the intestine.

The next time you go to the bathroom, pay attention to what you are doing – you might be surprised!

Not surprisingly, in children suffering from chronic constipation, the coordination of these processes gets very confused. First, they often do not get the urge to pass a bowel movement in the normal way, but rather, as pain or cramps. Second, when they start straining, instead of using all their muscles together to push the bowel movement out, they often push with some muscles and pull with others — they grunt and strain and seem to push as hard as they possibly can, but they are usually fighting against themselves. Finally, because they are pushing and straining so hard, rather than relaxing the external sphincter to let the bowel movement out, they often squeeze or tighten the sphincter. As a result, they must generate enough pressure to force the bowel movement through the closed sphincter. This is why some children with chronic constipation sometimes pass very thin bowel movements.

Not surprisingly, in children suffering from chronic constipation, the coordination of these processes gets very confused. First, they often do not get the urge to pass a bowel movement in the normal way, but rather, as pain or cramps. Second, when they start straining, instead of using all their muscles together to push the bowel movement out, they often push with some muscles and pull with others — they grunt and strain and seem to push as hard as they possibly can, but they are usually fighting against themselves. Finally, because they are pushing and straining so hard, rather than relaxing the external sphincter to let the bowel movement out, they often squeeze or tighten the sphincter. As a result, they must generate enough pressure to force the bowel movement through the closed sphincter. This is why some children with chronic constipation sometimes pass very thin bowel movements.