By Lisa Farr, M.Ed. Director, Exercise Physiology Core Lab

Interview with: Alex Dalrymple, MD, Department of Neurology

When you hear the name Michael J Fox, your mind might jump to the 80’s TV show Family Ties, but more than likely it goes to Parkinson’s disease. Michael J. Fox was diagnosed at age 29, and in the 20+ years since his diagnosis, has worked to reduce the burden of Parkinson’s with the creation of his foundation. Patients can turn to his foundation for support and answers, and researchers can apply for funding to study the disease. While progress has been made in the understanding of Parkinson’s, there is much work to be done and better treatments are needed. UVA is part of a multi-center study examining the role of exercise in slowing the progression of this disease. (For more information on the trial, including where the 27 sites are located, see https://www.sparx3pd.com.)

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that predominantly affects dopamine-producing nerve cells in a specific area of the brain. These dopaminergic neurons coordinate movement, and the loss of these cells due to Parkinson’s causes tremor, slowness, stiffness/rigidity, and difficulties with walking and balance. A person with Parkinson’s may have or develop over time a slow shuffling gait, difficulty with writing and other fine motor skills, decreased facial expression, and an involuntary shaking of a finger, hand, or limb. In addition to these motor symptoms, Parkinson’s may cause other signs and symptoms, such as low blood pressure, constipation, loss of smell, memory/thinking issues, mood disturbances, and sleep issues, such as acting out dreams. In fact, if a patient has all three of these signs—loss of smell, constipation, and acting out dreams—they have greater odds of developing Parkinson’s down the road.

There are therapies to reduce the symptoms of Parkinson’s, including dopamine-replacement medication. But the commonly used mediations have side effects when used long-term, such as dyskinesia (uncontrolled, involuntary writhing or wriggling movement) as well as “off” periods in which the medication is fading and the Parkinson’s symptoms are returning. In addition to medication options, some patients’ symptoms may benefit from deep brain stimulation or focused ultra sound.

Exercise can both regulate brain function and modify the symptoms of Parkinson’s. There is mounting evidence that it also protects against neurological damage. So in addition to improving fitness, function, balance, and movement, exercise protects the brain itself. A key chemical involved in this neuro-protection is BDNF. Exercise enhances the expression of BDNF, which is one reason it is effective at treating other brain-related disorders, such as depression and anxiety. Exercise also reduces inflammation.

The SPARX trial (NCT04284436) is a 28-site NIH-funded study that will examine the role of exercise—specifically, high intensity exercise versus more moderate exercise—in slowing the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Individuals between the ages of 40 and 80 who have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s recently and are not yet taking medication are eligible to enroll if they meet other study criteria. The UVA PI of the SPARX trial is Dr. Arthur Weltman, and his co-PI and study physician is Dr. Alex Dalrymple, a Neurologist who specializes in movement disorders. We sat down with Dr. Dalrymple to hear more about this important work.

Questions and Answers with Alex Dalrymple, MD

Question

Why did you want to study exercise as a therapy for Parkinson’s?

Answer

We have limited options for Parkinson’s disease. Our treatments improve symptoms but not the disease process itself. Exercise may be an exception—it may actually protect the brain and slow progression of the disease. We’ve known for a while that exercise is very beneficial for people with Parkinson’s but what is less clear is the best type of exercise…so our advice has been pretty general. When we prescribe medications, we are very precise on the dosing, yet with exercise we aren’t, just telling patients to remain active or walk more.

The most specific we’ve gotten is maybe to encourage boxing classes since that seems to be helpful in many ways. So the hope is that this study will allow us to have a better sense of exactly what patients should be doing if they are trying to slow down Parkinson’s. We know that any exercise is better than no exercise—but what’s best?

Question

So what is the real-life application of the SPARX trial? How will it help patients and the clinicians who care for them?

Answer

This is something we can offer patients—something that is beneficial across many levels, including hopefully the disease process itself. The longer a patient can retain function and quality of life without starting medication, or having to increase the dose of medication, the better.

Question

Your study will use something called a DaT scan. Can you tell us a little about this test, as well as some of the other measures you will look at in these subjects?

Answer

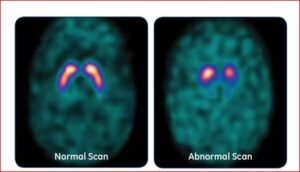

The DaT scan is a tool we have that helps confirm the diagnosis of Parkinson’s. It’s an imaging test that uses a radioactive tracer Ioflupan to allow us to see dopamine producing cells when we image the brain. The tracer is injected into the blood, where it circulates and makes it way to the brain. It attaches itself to dopamine neurons. Several hours later we image the brain to detect the tracer. People with Parkinson’s have a smaller signal than people without Parkinson’s. The below shows a DaT scan—the one on the left is from someone without Parkinson’s and the one on the right is from a patient with Parkinson’s disease.

The DaT Scan was approved for use over 10 years ago, but clinically we only tend to use it when the diagnosis isn’t clear—for example, does the patient have a benign tremor or Parkinson’s?

In this research study, once subjects have otherwise passed screening and a physical exam, it will confirm the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. We will also repeat the test at certain intervals to see if it is useful in tracking progression of disease.

In addition to the DaT scan we will test blood biomarkers, such as BDNF, and also inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, to see how those change over time with exercise at a moderate versus high intensity. A 6 minute walk test using special sensors called OPALS will be performed several times over the course of the study to look at things like movement patterns and stride length. A maximal exercise test called a VO2 peak will be performed several times throughout the study, both to guide the exercise prescription and to monitor improvements in fitness. Subjects will complete a number of surveys designed to evaluate their daily function, symptoms, and quality of life. Finally, we expect that some subjects may have to begin medication during the study. We will be interested in seeing if the need to start medication differs between the high intensity and moderate intensity exercise groups.

Question

Do subjects get to choose whether they will exercise at the moderate intensity or the higher intensity?

Answer

No, subjects are randomly assigned after they have passed all of the screening tests. The exercise intensity used for each subject is individualized based on the results of their treadmill test. So subjects will either be randomly assigned to 60 – 65% of maximal heart rate, or 80 – 85% maximal heart rate. Both groups will exercise 4 days per week. Their initial exercise sessions are supervised and then they have the option of joining a gym or exercising at home. Many of our potential subjects may not live in the Charlottesville area, so we needed to have exercise options that didn’t rely on them having to come to UVA to be supervised. We provide a stipend for gym memberships or home equipment.

Question

There are so many things that are interesting about this study, including the long follow up. What is the purpose of studying patients 6 months after the study has ended?

Answer

It is one thing to show that patients can exercise at the right level and make improvements when involved in a study with supervision and encouragement and support. It’s another to show that patients can sustain this once they are on their own. So this will be an interesting piece. If subjects show huge benefit during the study—do we still see this 6 months after the study has stopped? If so, is it because the patient continued to stick with the program? Does adherence to the program over the long haul allow the patient to keep the benefits—or even demonstrate new ones? We also hope to learn something about what makes patients stick with it, and what barriers make it hard to do so.

While catching up with Dr. Dalrymple we took the time to get a little personal too.

Question

Dr. Dalrymple, you obviously believe in exercise. Is this a way of life for you?

Answer

The honest answer is—not always as much as I’d like it to be. I’m a very active person—I walk my dog every day, and try to play outside with my kids—but I am only getting to the gym maybe twice per week. Some weeks are better but not every week. My wife Sarah is a physician too, and our kids are 1 and 3…and what we are realizing is that if we don’t make it a priority in our schedules it’s just not going to happen as often as it should. When I counsel my patients about exercise—which I do at every visit—and I tell them I get that it can be hard to find time…I truly mean it. I understand the challenges.

Question

What made you choose neurology as your specialty?

Answer

In my third year of medical school I was on day 12 of a 14 day rotation in Neurology and I realized how excited I was go to work that day. That was the main thing. But also—I find the brain fascinating.

For more information on the SPARX trial, or to refer a patient, contact Dr. Alex Dalrymple WAD5G@hscmail.mcc.virginia.edu, or study coordinator Lauren Miller FDK5DN@hscmail.mcc.virginia.edu