By Lisa Farr, M.Ed. Director, Exercise Physiology Core Lab

Interview with: Christopher Kramer, MD, George A. Beller MD Distinguished Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine; Chief, Cardiovascular Division

We know that athletes develop larger hearts that can contract powerfully during sport when needed. This normal, expected physiological result of exercise is called, appropriately, “athlete’s heart.” But sometimes a large heart isn’t a sign of athletic fitness but rather of a pathological heart condition.

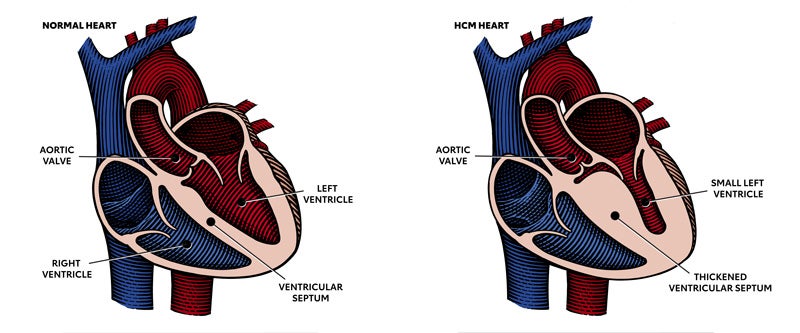

One of these conditions is obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or oHCM. Obstructive HCM is an inherited condition in which the heart muscle in the left ventricle becomes abnormally thickened, which can block blood flow out of the heart to the body. This obstruction causes the heart muscle to work harder to pump blood to the body and can cause symptoms of chest pain, dizziness, shortness of breath and fainting.

oHCM is characterized by abnormal cardiac muscle cell function. Sarcomeres are the muscle cell units responsible for contraction and relaxation of the heart. In oHCM, the units of the sarcomere—called actin and myosin—do not function normally and do not contract and relax in the expected manner. A HCM heart is characterized by “hyper contraction,” impaired relaxation, and structural thickening of the walls, often the septum, which is the wall that separates the two ventricles of the heart. In addition to exercise intolerance, patients with obstructive HCM may develop heart failure.

Patients with oHCM are typically evaluated with a stress echocardiogram test to determine fitness, exercise tolerance, how their obstruction responds to exercise, and whether they develop heart arrhythmias during exercise. Patients with this condition have a higher risk of abnormal heart rhythms while exerting themselves. Because of this risk, patients with a diagnosis of oHCM have historically been told to avoid exercise. But restricting exercise has its own set of consequences, often creating a downward spiral in which the patient does less, sits more, and gains weight—all of which contribute to worsening exercise tolerance and cardiovascular health.

oHCM patients have traditionally been treated with medications like beta blockers that reduce the heart’s workload, as well as surgery or invasive procedures that reduce the amount of thickened heart tissue. A few years ago, a new class of drug was developed, and UVA was one of the testing sites. This new class, called a cardiac myosin inhibitor, directly and selectively inhibits myosin, a cardiac muscle cell protein that promotes hypercontractility. This was a new approach in that the drug actually worked on the cause of the cardiac dysfunction and not just symptoms. Subjects randomized to the drug had an improvement in cardiovascular fitness, symptoms, and heart failure classification, and showed positive changes on the echo (reduced LV ouflow gradient) and MRI (reverse remodeling characterized by a reduction in the wall thickness).

In other words, this medication helped the heart function more normally and actually changed the structure of the heart without surgery. The end result for the patient was that they felt better and were more able to tolerate exercise.

Another myosin inhibitor is now under evaluation and UVA is excited to be one of 80 sites worldwide participating. We caught up with study PI Christopher Kramer, MD, to learn more about this important work.

Questions and Answers with Christopher Kramer, MD

Question

Why did you want to study this issue?

Answer

We have a few therapies that are modestly effective…but don’t always make patients feel much better. This new class of medication reduces the outflow gradient seen in obstructive HCM, which allows patients to feel less short of breath with exercise. This allows patients to do more, lead a more normal life that includes exercise. Exercise and activity are so important for mental and physical health.

Also, the hope is that as these newer drugs are developed, costs may go down since there would ultimately be several available.

Question

So what is the real-life application of your study?

Answer

An effective pill therapy could delay or prevent the need for surgery and other procedures. It should help improve quality of life, ability to exercise, and physical function. We used to restrict all but the lightest exercise in HCM due to concern over risks. But prohibiting people from leading physically active lives has its own risks. Patients were told to avoid exercise, and so they became sedentary and obese. This isn’t good for health! (or quality of life)

Several studies about exercise and HCM have been published in the past few years and have been reassuring. So while we still don’t recommend competitive sports at the professional or collegiate level, most are safe to exercise recreationally. Some of the studies have used supervised exercise, but a recent one was internet-based. The data are encouraging and will hopefully make cardiologists more comfortable recommending moderate exercise to HCM patients.

Question

Can you describe the study?

Answer

UVA is one of 80 sites worldwide involved in this study. We are enrolling subjects between 18 and 85 years of age with oHCM who meet certain criteria re: their heart thickness, their outflow gradient, and their symptoms. Eligible subjects will be randomized to either the study drug or a placebo. Subjects will receive a number of tests, including labs and echo. Some will also receive a cardiac MRI. They’ll take surveys about their symptoms with activity. They’ll have a maximal exercise test on a treadmill—called a VO2 peak, or CPET. This is one of the most important measures in the study. VO2 peak is the gold standard test of cardiorespiratory function and fitness. The VO2 peak will be repeated down the road, after the subject takes the drug or a placebo for 24 weeks. The hope is that VO2 peak will improve in those taking the drug, along with their symptoms, heart failure classification, quality of life, labs, and echo/MRI measures.

The study is UVA HSR 210472 and is entitled A Phase 3, Multi-Center, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of CK-3773274 in Adults with Symptomatic Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction

To refer a patient, contact the study coordinator Caroline Flournoy, Ph.D, CLF4W@hscmail.mcc.virginia.edu

While catching up with Dr. Kramer, we took the time to get a little personal too.

Question

Dr. Kramer, you clearly believe in the power of exercise. What type do you do?

Answer

When I was younger I played ice hockey, soccer, and tennis. I was a coxswain in college. As I got older I gravitated towards swimming, cycling, hiking, and golf. I have a genetic hip condition and I knew it would give me more and more trouble as I got older. I knew I would have to have hip replacement surgery at a young age. Being an exerciser allowed me to put it off as long as possible, and also to return to normal function more easily after my surgery. I did physical therapy religiously, and have returned to doing many of my favorite things. I have a peloton bike at home, which is really useful for getting a good work out without aggravating the one hip that hasn’t been replaced yet.

Question

We’ve talked to a lot of physicians who were so busy in residency and fellowship that they didn’t make time for exercise. Was this you?

Answer

(He smiles) No, I use to trade call with my co-residents and fellows so that I could make my ice hockey games.

Question

Do you have any advice to others?

Answer

Listen to your body. Do what you need to do to take care of it. Stay as active as you can.

Out for a hike